In

Overcoming Overeating, Jane Hirschmann and Carol Munter presented one of the first guides for intuitive eating, namely eating when you’re hungry and stopping when you’re full. As they contend, a compulsive eater is not addicted to food, but to the diet-binge cycle. Their theory purports that overeating results from overly rigid (diet) standards, and that it is your (healthy) way of asserting yourself. Hirschmann and Munter write:

You the hopeless case feel out of control and despondent because you’ve bought the line that you’re a failure at the idealized task of body shaping. But you the rebel are a success. You break the rules and assert your right to eat what you want and look as you do. The compulsive eater is, in an interesting way, a rebel in constant protest against what has, by now, become her own imposition of cultural standards and judgments.

Their approach allows you to eat whatever you’re craving in a given moment and focuses on equalizing different kinds of food, so that you can arrive at a place where a carrot has the same value as a slice of carrot cake. Whenever you’re hungry, you’re encouraged to ask yourself what you’re craving: Something sweet? Salty? Crunchy? Mushy? Hot? Cold? And, you’re encouraged to eat exactly what you’re craving. Time and time again, Hirschmann and Munter (in their clinical work) have found that people may make some unhealthy choices early on, but eventually their bodies regulate and they begin to crave, at different times, foods across the spectrum.

Other aspects of Hirschmann and Munter’s approach include:

1) Carrying around a food bag, stocked with different types of food, in order to prevent those moments of excessive hunger that lead to overeating.

2) Cleaning out your closet to reflect your current weight—either giving away or hiding the clothing that no longer fits, since seeing it on a daily basis is a reminder that you’ve “failed.”

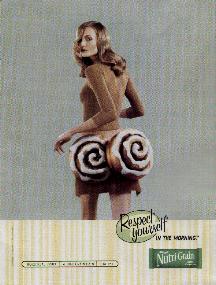

3) Stocking your home with an array of foods, including what they call “formerly forbidden foods.” The theory is that by exposing yourself to foods that you used to deny yourself, you’ll, over time, reduce their “glitter,” and, consequently, their grip on you. As for amounts? Hirschmann and Munter encourage you to have, on hand, three times the amount of food that you’re capable of eating in a binge. Ideally, it’s all in a single container (think stuffing three bags of Oreos into a large plastic container), so that you’re not able to get caught up in amounts (“I’ve now eaten an entire row”), but instead can focus on what your body wants. We tend to overeat when we know there’s a limited amount (possibly a relic of dieting, in which we’re stocking up before a self-imposed draught).

4) Thinking beyond meals—eating when you’re hungry and not around a preordained schedule. In practice, this results, typically, in more than three “eating experiences” per day.

5) Engaging in “mirror work,” in which you practice looking at your body, without judgment.

6) Working at distinguishing between “stomach hunger” (when you’re physiologically hungry) and “mouth hunger” (when you’re craving food out of boredom, anxiety, anger, loneliness, or any other motivation that doesn’t involve physiological hunger) and, over time, arriving at a place where you’re eating more frequently out of stomach hunger and able to identify mouth hunger and why you might be experiencing it.

7) Tossing the scale.

Various aspects of this approach (or the approach in its entirety) may seem ridiculously radical, particularly in a culture that preaches regular meals, precision, restriction, monitoring, and self-loathing. Certainly, it won’t work for everyone. But, I’ve found that it can be quite helpful for women who have historically cycled through the diet-binge chain, who would like to disempower the hold that food has on their lives, and who are interested in promoting a body image governed by self-acceptance.